As part of our series on the APCC Special Report "Structures for a climate-friendly life", Martin Auer from Scientists for Future Austria with Professor Andreas Novy spoken. His subject is social economy and he heads the Institute for Multi-Level Governance and Development at the Vienna University of Economics and Business. We talked about the chapter “Degrowth and the political economy of growth imperatives”.

The interview can be heard on Alpine GLOW.

It is evident that humanity as a whole is reaching the limits of the planet. Since the 1960s, we've been consuming more resources in a year than the planet can regenerate. This year, World Overshoot Day is at the end of July. Countries like Austria consume their fair share much earlier, this year it was April 6th. Since then we have been living at the expense of the future. And it's not just because the number of people on the planet is increasing. Every single person consumes more and more. On average, per capita income has quadrupled since the 1950s. This prosperity is distributed very unequally, both between countries and within countries, but overall we are at a point where every sensible housewife and every sensible househusband should say: That's enough, we can't do more.

But every Treasury Secretary and corporate executive frowns when economic growth slows. What is it, what is driving this growth so relentlessly? Why can't we just say: There is enough for everyone, it just has to be distributed differently, then it's enough?

What is capitalism?

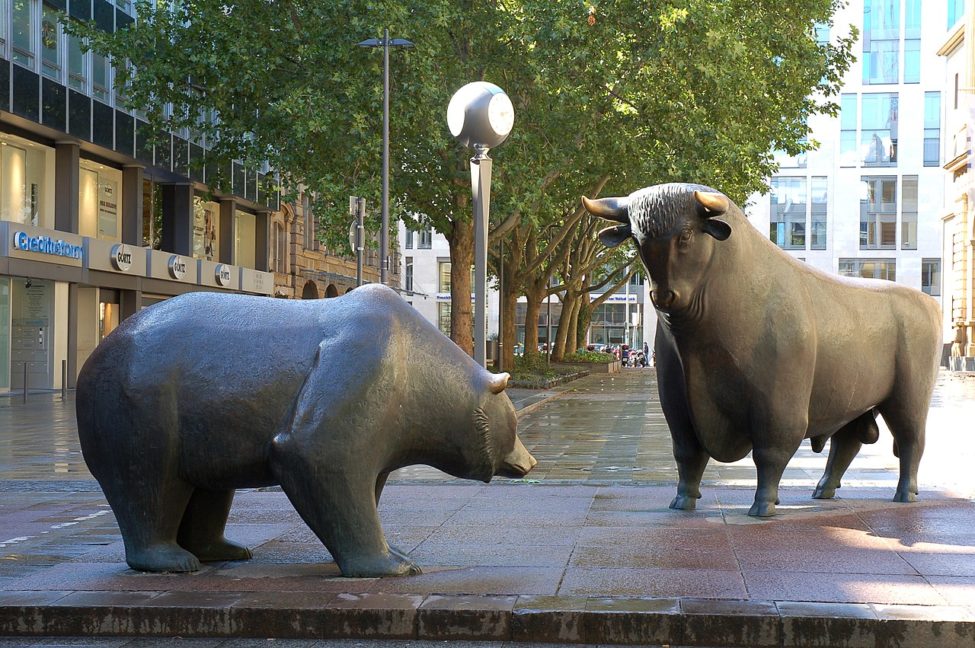

Photo: Eva Kroecher via Wikimedia,, CC BY-SA

Martin Auer: The APCC Special Report reads: “The transgression of planetary boundaries that can currently be observed (e.g. in the case of climate change) is closely related to the capitalist mode of production and life. So my first question is: What is this capitalist mode of production, what characterizes it and how does it differ from previous modes of production?

Andreas Novy: Up until the 17th and 18th centuries, economies around the world were more or less stable and organized in cycles. There was little or no growth in goods production and population. And that changes with the capitalist economy. This makes the capitalist economy so unique that technical changes - the steam engine, fertilizers - but also organizational changes, above all the division of labor and the resulting and broadening of market economies - trigger a productivity boost and a growth spurt that is unique and has continued for two centuries and has meant that not only has national income multiplied, that people are much richer today, but there are also many more people who are living longer, who are living much healthier, who are more educated. That means modern society, not only in the Global North, cannot be compared to societies three hundred years ago. That depends on this capitalist economy, on the way people produce and live. And that has a number of positive aspects for all of us.

The big acceleration

And at the same time, natural science and earth science have established that since the twentieth century and especially since the middle of the twentieth century, there has been something like a great acceleration, i.e. a massive exponential growth of socio-economic and scientific indicators - from GDP to CO20 emissions. And that this biophysical growth, the excessive consumption of resources, the excessive access to nature, begins to undermine the basis of life for human and especially non-human life. And the destructive elements of growth are beginning to be perceived more strongly, to the point that climate research is now also becoming convinced that this type of economy is one of the main causes of the climate catastrophe, and that a climate catastrophe can only be avoided if we succeed to transform this economy in the 2st century.

In capitalism, stagnation is downfall

Martin Auer: Who is driving this growth compulsion? Is it because consumers want more and more, or is it economic policy, or does it come from individual companies, or is it related to competition between companies?

Andreas Novy: It is a structure that has emerged here that has established competitive relationships through the creation of markets. Competitive relationships are an incentive to improve, to gain market share, to advance technological progress in order to survive against the competition. And in capitalism the guiding principle applies: standstill is downfall. That is why players are doomed to think in terms of growth, because only if they improve, grow, gain market share can they assert themselves. Therefore, overcoming the capitalist mode of production requires that we change structures. It always makes sense to appeal to individuals. Companies that are listed on the stock exchange will not be deterred. In other words, it would be necessary to break through this logic. What is required is a way of doing business in which the focus is not on profit. That should continue, but the essential, fundamental decisions should be based on what is needed for a good life.

Alternatives to capitalism?

Martin Auer: But that would definitely require very strong regulations – from state or supranational levels. But would it also require a shift from private-sector companies to more municipal companies, or state-owned companies? If we say a private company can't afford not to grow, what's the alternative?

Andreas Novy: The discussion about capitalism and the alternatives to capitalism is of course very old, and the strongest and most well-known alternative was – is socialism, and the most well-known alternative to the market economy is central planning.

Martin Auer: But it wasn't that satisfactory either.

Andreas Novy: Exactly. What is very unsatisfactory about these debates is that they always think in terms of dualisms. It's really bad to think that the opposite of something you don't like is the right thing to do. The approaches that I consider to be significantly more promising are always mixed-economy approaches. I believe that a post-capitalist economy is mixed, accepting that different sectors of the economy operate on different logics. There are certain areas that can be organized very well as a market economy, for example restaurants. So it makes a lot of sense that people can choose whether they eat pizza or schnitzel, and that better cooks prevail over worse cooks. And then there are other areas, such as education and health, where provision by the public sector is almost certainly better. And then there are still areas where you can see if you can't satisfy needs without consumption and without money. That you have a city of short distances and meeting areas where you don't need a car, and that the economy is shrinking because people no longer have to spend on mobility.

The fear of shrinking

Martin Auer: But that is now a word that triggers fear: the economy is shrinking. Everyone gets goosebumps: Unemployment, loss of income... How do you see that?

Andreas Novy: That's very understandable. Not only because economic growth has produced social prosperity here in Austria. Also because economic growth finances a welfare capitalism, a developed welfare state. That means there are very real problems in transitioning to an economy where growth is no longer the driver. This not only means that a few unnecessary products are produced less, but also requires changes in the social system. It's more than understandable that people are worried about this. But if you look at the numbers, there are a few points that help: one is that the form of provision of social services that is more compatible with the climate and more compatible with sustainable development is to limit overconsumption. So inequality is a very important driver that undermines social cohesion, but also transcends planetary boundaries.

Martin Auer: How can you do that?

Andreas Novy: You can do that by doing what worked very quickly and effectively, by identifying the Russian oligarchs, who then sanctioned everyone because they sympathize with the Russian regime, that you follow this principle, that there are people who consume excessively, that limits are set here that have to be set by society, where these limits are, whether it's the illegal bank accounts, whether it's the yachts, and then you can consider whether you regulate it through taxes, or whether you that regulates bans, that private flying is no longer allowed, all of that should be negotiated, but it is an essential starting point for shrinking. And that is a shrinking in a corner that does not affect the normal population.

Martin Auer: But this is now starting with consumption, not with the production method.

Andreas Novy: If you start with the way of production, it's very similar, it's about shifting dividends and returns to wages. Again, this is a redistribution measure, that there is a shift from income to leisure and time wealth. This means that you have more time to do certain things yourself or otherwise maintain your standard of living, and that it is due to a shift from production geared towards consumption, which is then consumed by private individuals, towards investments in infrastructure , which permanently satisfy needs without people having to buy things in return.

Climate friendliness should make life cheaper

Martin Auer: What would be an example of that?

Andreas Novy: meeting zones. Public recreation spaces that change the concept of vacation, change that concept of weekend escape from the city. This is the first classic and most obvious example, which can of course be quickly extended to culture and other areas. And it is an important area because the two most important climate-relevant types of consumption are mobility and housing. Creating the opportunity for people to have a smaller private living space because the living environment is of such high quality is a huge contribution to climate protection. It implies a shrinking because the construction industry is no longer building new houses but is renovating houses. It implies a shrinking because far fewer cars are being produced because they are mainly for car sharing and the buses needed are fewer than private cars. But on the quality of life side, that means you can get by on significantly less income.

Martin Auer: So with fewer things actually.

Andreas Novy: With fewer things, but also that you can get by with less income because your living costs are lower in a quality neighborhood. You have to spend less to get somewhere by car, you have to spend less on your apartment, and with that you already have a substantial part of the costs of a household.

Martin Auer: But that also requires social security. If we now say that people no longer need a car because the city is built accordingly, and we have 75.000 people in Austria in the car industry, how do we deal with that now?

Andreas Novy: It's probably easier in the construction industry, where you have a transformation from new construction to renovation in all variants: upgrading towards low-energy houses, insulation, photovoltaics and all that. The automotive industry, the mobility sector is certainly an area that will simply shrink. But it is quite clear that there are other areas where workers are urgently needed. That is also present in the public debate, and it is not just the care sector...

Martin Auer: But you can't just retrain a car worker to be a nurse. This can happen over a long period of development, but not instantaneously.

Andreas Novy: Exactly. Therefore it will also be necessary to a greater extent to treat these different economic sectors differently. It will be necessary to accompany the transformation of the mobility system, it will be necessary for the state to play an important role, and it is actually – there are many examples – naïve to believe that car workers will then become carers. But, to put it the other way around, there are trams and railways that have to be built, and there are other technical professions where it's more realistic for car mechanics to go, and that will have to be supported. If you want to maintain social cohesion on the way to a post-capitalist society, you cannot avoid state support.

Who should decide what is enough?

Martin Auer: But who is to decide now what is enough? When we speak of sufficiency: what is sufficient, how can this be determined and how can this be enforced?

Andreas Novy: That's actually settled. We live in a liberal democracy where this happens all the time. One of the most catastrophic events for the climate is the road traffic regulations - I believe from 1960 in Austria - which introduced an unbelievable prohibition regime that on the road other road users who are not driving are only allowed to a very limited extent to get around to move. This is based on laws, it is specified by the legislature. We have compulsory schooling and all sorts of rules and regulations, you are not allowed to steal property and so on, in a liberal democracy that is regulated by the legislature, the government, however the powers are regulated. And with that, enough and a limit are constantly set. And if we now want there to be more meeting zones, then that means that it will mean certain limits for driving and a certain enough. And if we have to renaturate areas, then that will probably also include the dismantling of roads and airports, and then a government will decide, just as it has now pushed for a third runway. It is very clear, and I would see that as the only way, that this can only be done democratically, and that it is therefore also necessary for the population to want it and support it, which is of course a huge challenge.

Martin Auer: But that still requires a lot of information and a lot of motivation.

Andreas Novy: Exactly. And of course we are a long way from that, but it also means that we are on the path to which there is no alternative. I think it's completely a specter of climate deniers and climate delayers to speak of eco-dictatorships. I see the much greater danger in the fact that there are authoritarian-dictatorial strategies to push the logic of growth unhindered for a few more years and to prevent climate measures. I believe that the big challenge is: can we implement effective climate action in a democratic community. There is a question mark over whether this will succeed, but in my opinion there is no alternative.

Martin Auer: Thank you, I think that was a good ending.

Andreas Novy: Yes gladly.

Cover photo: pixfuel

This post was created by the Option Community. Join in and post your message!