It is well known that low-income people cause fewer greenhouse gas emissions than high-income people. This inequality continues to grow, as the latest report by economist Lucas Chancel of the World Inequality Lab shows. This institute is based at the Paris School of Economics, with economist Thomas Piketty ("Capital in the 21st Century") in a senior position.

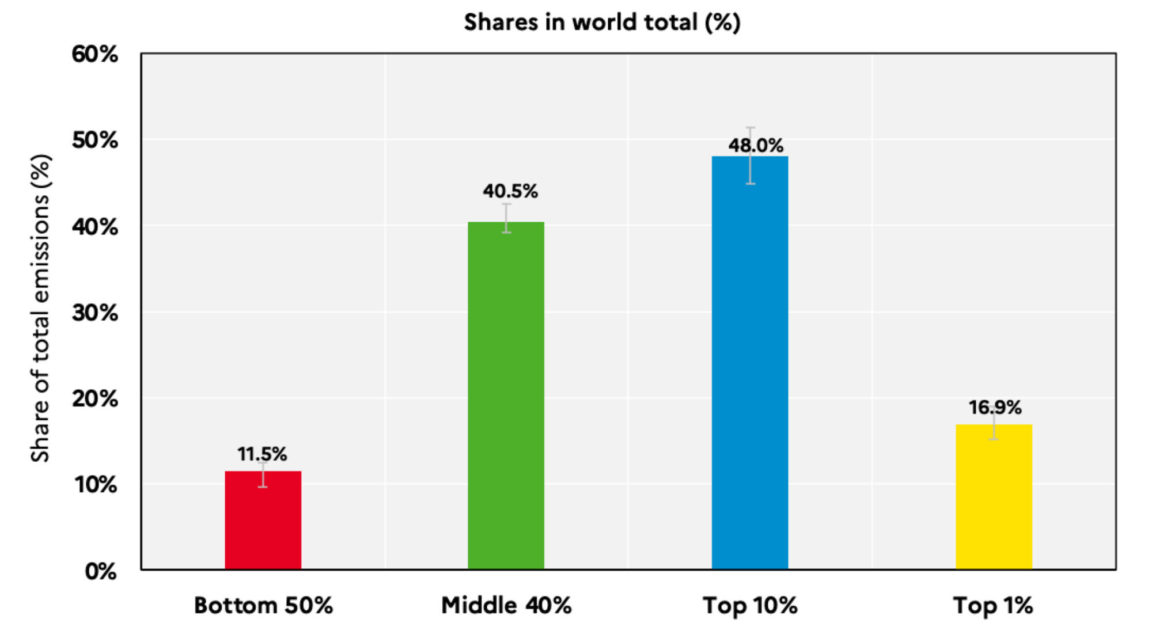

According to the 2023 Climate Inequality Report1, the poorest half of the world's population is responsible for only 11,5% of global emissions, while the top 10% cause almost half of the emissions, 48%. The top 16,9 percent is responsible for XNUMX% of emissions.

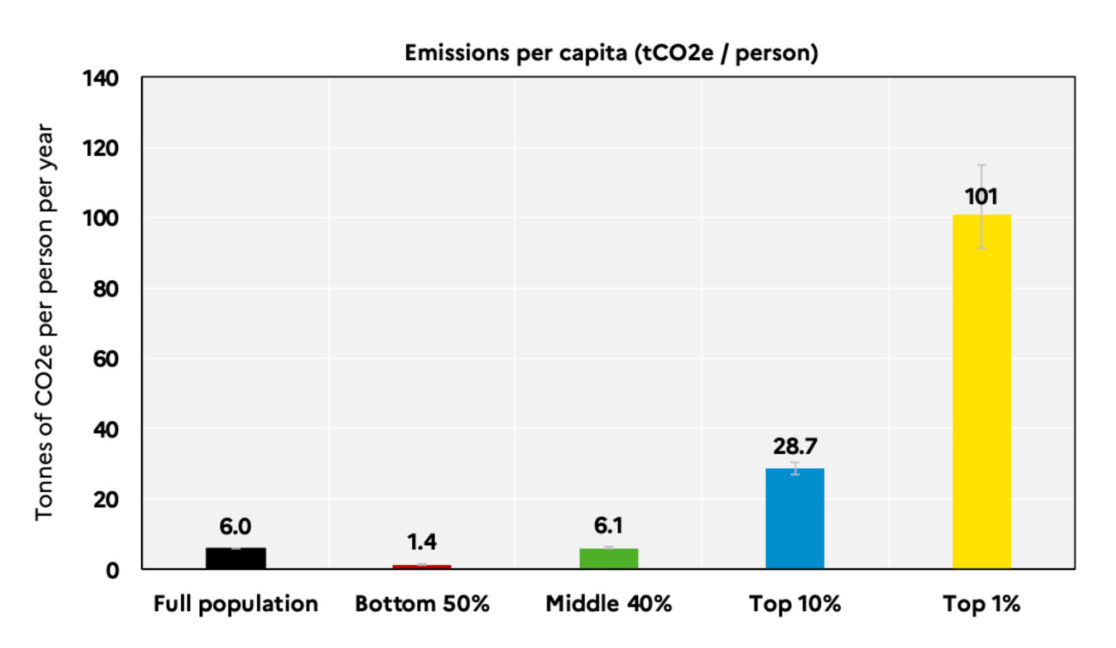

The differences become even more blatant if you look at the per capita emissions of the various income groups. In order to reach the 1,5°C target, every inhabitant: in the world should cause only 2050 tons of CO1,9 per year by 2. In fact, the poorest 50% of the world's population remains well below that limit at 1,4 tons per capita, while the top 101% exceeds that limit by 50 times at XNUMX tons per capita.

From 1990 to 2019 (the year before the Covid-19 pandemic), per capita emissions from the poorest half of the world’s population increased from an average of 1,1 to 1,4 tonnes of CO2e. Emissions from the top 80 percent have increased from 101 to XNUMX tons per capita over the same period. The emissions of the other groups have remained about the same.

The share of the poorest half in total emissions has increased from 9,4% to 11,5%, the share of the richest one percent from 13,7% to 16,9%.

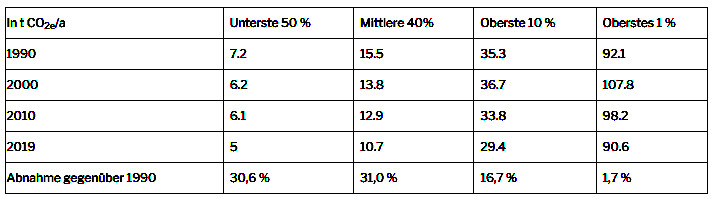

In Europe, per capita emissions fell overall from 1990 to 2019. But a look at the income groups shows that the emissions of the poorest half and the middle 40 percent have each fallen by around 30%, the emissions of the top 10 percent by only 16,7% and those of the richest 1,7 percent by only 1990% . So progress has mainly been at the expense of lower and middle incomes. This can be explained, among other things, by the fact that these incomes hardly increased in real terms from 2019 to XNUMX.

If in 1990 global inequality was mainly characterized by the differences between poor and rich countries, today it is mainly caused by the differences between poor and rich within countries. Classes of the rich and super-rich have also emerged in low- and middle-income countries. In East Asia, the top 10 percent cause significantly more emissions than in Europe, but the bottom 50 percent significantly less. In most regions of the world, the poorer half's per capita emissions are close to or below the limit of 1,9 tons per year, except in North America, Europe and Russia/Central Asia.

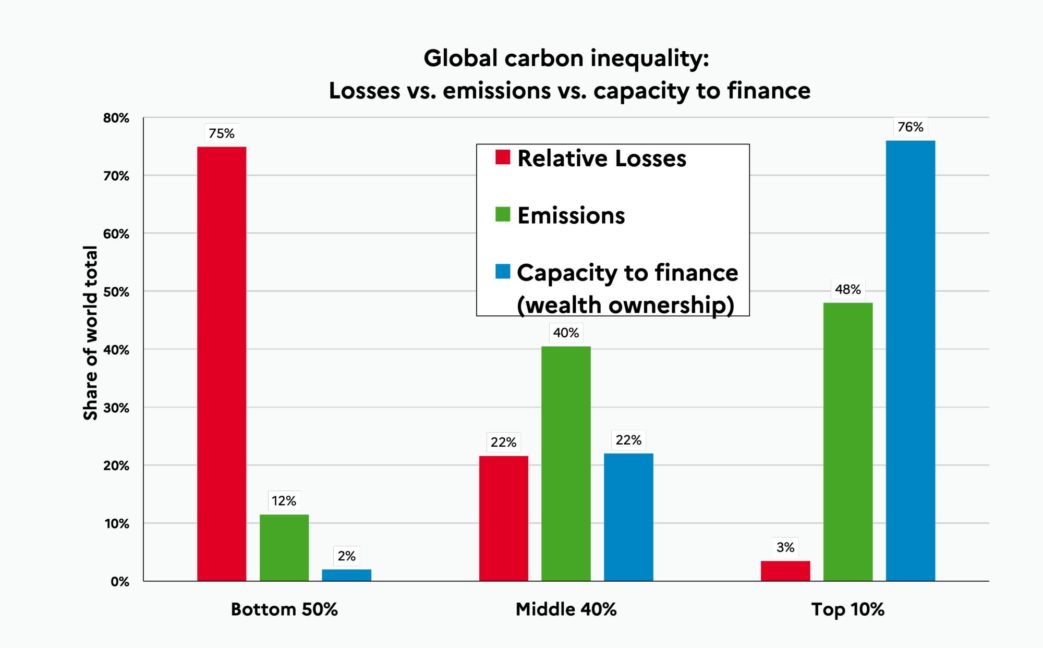

At the same time, the poorest are much more affected by the consequences of climate change. Three-fourths of the income losses from droughts, floods, wildfires, hurricanes and so on hit the poorest half of the world's population, while the richest 10% suffer only 3% of the income losses.

The poorest half of the population owns only 2% of global wealth. They therefore have very little means at their disposal to protect themselves from the consequences of climate change. The richest 10% own 76% of the wealth, so they have many times more options.

In many low-income regions, climate change has reduced agricultural productivity by 30%. More than 780 million people are currently at risk from severe flooding and the resulting poverty. Many countries in the Global South are now significantly poorer than they would be without climate change. Many tropical and subtropical countries could experience income losses of more than 80% by the turn of the century.

Potential impact of poverty reduction on greenhouse gas emissions

At the top of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs2) for 2030 stands for the eradication of poverty and hunger. Would eradicating global poverty put a significant strain on the CO2 budget that is still available to us to achieve the Paris climate targets? The study presents calculations of how higher incomes for the poorest would increase their greenhouse gas emissions.

The report's calculations refer to the poverty lines that the World Bank used as a basis for its estimates between 2015 and 2022. In September, however, the World Bank set new poverty lines to take account of rising prices for essential goods. Since then, an income of less than USD 2,15 per day has been regarded as extreme poverty (previously USD 1,90). The other two limits are now USD 3,65 for “lower-middle income countries” (previously USD 3,20) and USD 6,85 for “upper-middle income countries” (previously USD 5,50). However, these income limits correspond to the previous ones in terms of purchasing power.

Living in extreme poverty in 2019 according to the World Bank3 648 million people4. Raising their incomes to the lowest minimum would increase global greenhouse gas emissions by about 1%. In a situation where every tenth of a degree and every ton of CO2 counts, this is certainly not a negligible factor. Almost a quarter of the world's population lives below the median poverty line. Raising their incomes to the middle poverty line would increase global emissions by about 5%. Undoubtedly a significant burden on the climate. And raising the incomes of almost half the population to the upper poverty line would increase emissions by as much as 18%!

So is it impossible to eradicate poverty and avert climate collapse at the same time?

A look at Figure 5 makes it clear: The emissions of the richest one percent are three times what eliminating the median level of poverty would cause. And the emissions of richest ten percent (see Figure 1) are a little less than three times what would be needed to provide all people with a minimum income above the upper poverty line. Eradication of poverty thus requires a massive redistribution of carbon budgets, but it is by no means impossible.

Of course, this redistribution would not change the total global emissions. The emissions of the rich and affluent must therefore be reduced beyond this level.

At the same time, fighting poverty cannot just consist of giving people the opportunity to increase their income. According to neoliberal economic ideology, the poorest would have the opportunity to earn money if more jobs were created through economic growth5. But economic growth in its current form leads to a further increase in emissions6.

The report cites a study by Jefim Vogel, Julia Steinberger et al. about the socio-economic conditions under which human needs can be satisfied with little energy input7. This study examines 106 countries on the extent to which six basic human needs are met: health, nutrition, drinking water, sanitation, education and minimum income, and how they relate to energy use. The study concludes that countries with good public services, good infrastructure, low income inequality and universal access to electricity have the best opportunities to meet these needs with low energy expenditure. The authors see universal basic care as one of the most important possible measures8. Poverty can be alleviated through higher monetary income, but also through a so-called “social income”: Public services and goods that are made available free of charge or cheaply and are ecologically compatible also relieve the burden on the wallet.

An example: Around 2,6 billion people around the world cook with kerosene, wood, charcoal or dung. This leads to catastrophic indoor air pollution with dire health consequences, from chronic coughs to pneumonia and cancer. Wood and charcoal for cooking alone cause emissions of 1 gigatonne of CO2 annually, around 2% of global emissions. The use of wood and charcoal also contributes to deforestation, which means that firewood has to be transported over ever greater distances, often on women's backs. So free electricity from renewable sources would simultaneously alleviate poverty, promote good health, lower health care costs, free up time for education and political participation, and reduce global emissions9.

Photos: M-Rwimo , Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

Other proposals are: setting minimum and maximum incomes, progressive taxes on wealth and inheritance; the shift to ecologically more favorable forms of satisfying needs (the need for warmth can be satisfied not only through heating but also through better insulation, the need for food through plant-based rather than animal-based foods), the shift in transport from individual to public transport, from motorized to active Mobility.

How can poverty reduction, climate change mitigation and climate change adaptation be funded?

Rich countries need to step up their development cooperation efforts, say the authors. But international transfers will not be enough to tackle global climate inequality. Profound changes in national and international tax systems will be required. In low- and middle-income countries, too, the income that could be used to support vulnerable groups should be generated through progressive taxes on capital income, inheritance and wealth.

The report cites Indonesia as a successful example: In 2014, the Indonesian government drastically cut fuel subsidies. This meant higher revenues for the state. but also higher energy prices for the population, which initially provoked strong resistance. However, the reform was accepted when the government decided to use the proceeds to fund universal health insurance.

Tax revenues of multinational companies

The international rules for the taxation of multinational corporations should be designed in such a way that taxes on profits made in low- and middle-income countries also benefit those countries in full. The 15 percent global corporate tax minimum, modeled on the OECD model, would largely benefit rich countries where the corporations are based, rather than the countries where the profits are made.

Taxes on international air and sea traffic

Levies on air and sea transport have been proposed several times in the UNFCCC and other fora. In 2008, the Maldives presented a concept for a passenger tax on behalf of the small island states. In 2021, the Marshal Islands and Solomon Islands proposed a shipping tax to the International Maritime Organization. At the climate summit in Glasgow, the UN Special Rapporteur on Development and Human Rights took up the suggestions and emphasized the responsibility of "wealthy individuals". According to his report, the two levies could bring between $132 billion and $392 billion annually to help small island and least developed countries cope with loss and damage and climate adaptation.

A wealth tax for the super-rich in favor of climate protection and adaptation

Around 65.000 people (just over 0,001% of the adult population) have wealth of more than USD 100 million. A modest progressive tax on such extreme fortunes could raise the funds for the necessary climate adaptation measures. According to the UNEP Adaptation Gap Report, the funding gap is USD 202 billion annually. The tax Chancel is proposing starts at 1,5% for assets of $100 million up to $1 billion, 2% up to $10 billion, 2,5% up to $100 billion, and 3% for everything lies above. This tax (Chancel calls it “1,5% for 1,5°C”) could raise $295 billion annually, almost half the funding needed for climate adaptation. With such a tax, the US and European countries together could already raise USD 175 billion for a global climate fund without burdening 99,99% of their population.

If the tax were to be levied from USD 5 million - and even that would only affect 0,1% of the world's population - USD 1.100 billion could be collected annually for climate protection and adaptation. Total financing needs for climate change mitigation and adaptation up to 2030 for low- and middle-income countries excluding China are estimated at USD 2.000 to 2.800 billion annually. Some of this is covered by existing and planned investments, leaving a funding gap of $1.800 billion. So the tax on wealth over $5 million could cover a large portion of that funding gap.

Spotted: Christian Plas

cover photo: Ninara, CC BY

Tables: Climate Inequality Report, CC BY

Notes

1 Chancel, Lucas; Bothe, Phillip; Voituriez, Tancrede (2023): Climate Inequality Report 2023: World Inequality Lab. On-line: https://wid.world/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/CBV2023-ClimateInequalityReport-3.pdf

2 https://www.sdgwatch.at/de/ueber-sdgs/

3 https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/half-global-population-lives-less-us685-person-day

4 The pandemic has pushed an additional 2020 million people below the poverty line in 70, bringing the number to 719 million. The poorest 40% of the world's population lost an average of 4%: of their income, the richest 20% only 2%: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2022/10/05/global-progress-in-reducing-extreme-poverty-grinds-to-a-halt

5 ZBDollar, David & Kraay, Art (2002): “Growth is good for the poor”, Journal of Economic Growth, Vol. 7, no. 3, 195-225. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40216063

6 See our post https://at.scientists4future.org/2022/04/19/mythos-vom-gruenen-wachstum/

7 Vogel, Yefim; Steinberger, Julia K.; O'Neill, Daniel W.; Lamb, William F.; Krishnakumar, Jaya (2021): Socio-economic conditions for satisfying human needs at low energy use: An international analysis of social provisioning. In: Global Environmental Change 69, p. 102287. DOI: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102287.

8 Coote A, Percy A 2020. The Case for Universal Basic Services. John Wiley & Sons.

9 https://www.equaltimes.org/polluting-cooking-methods-used-by?lang=en#.ZFtjKXbP2Uk

This post was created by the Option Community. Join in and post your message!