How can the transition to a climate-friendly life in Austria be made possible? This is what the current APCC report “Structures for a climate-friendly life” is about. He does not look at climate change from a scientific perspective, but summarizes the findings of the social sciences on this question. Dr. Margret Haderer is one of the authors of the report and was responsible, among other things, for the chapter entitled: "Prospects for the analysis and design of structures for climate-friendly living". Martin Auer talks to her about the different scientific perspectives on the question of climate-friendly structures, which lead to different problem diagnoses and also to different solution approaches.

Martin Auer: Dear Margret, first question: what is your area of expertise, what are you working on and what was your role in this APCC report?

Margaret Haderer: I am a political scientist by training and in the context of my dissertation I actually did not deal with climate change, but with the housing issue. Since I returned to Vienna – I was doing my PhD at the University of Toronto – I then did my postdoc phase on the topic of climate, a research project that looked at how cities react to climate change, especially what governing cities. And it was in this context that I was asked to write the APCC Report against the background of my engagement with environmental issues. That was a collaboration of about two years. The task for this chapter with the unwieldy name was to explain which dominant perspectives there are in the social sciences on the shaping of climate change. The question of how structures can be designed in such a way that they become climate-friendly is a social science question. Scientists can only give a limited answer to this. So: How do you bring about social change in order to achieve a certain goal.

Martin Auer: You then divided that into four main groups, these different perspectives. What would that be?

Margaret Haderer: At the beginning we looked through a lot of social science sources and then came to the conclusion that four perspectives are quite dominant: the market perspective, then the innovation perspective, the provision perspective and the societal perspective. These perspectives each imply different diagnoses – What are the societal challenges related to climate change? - And also different solutions.

The market perspective

Martin Auer:: What are the emphases of these different theoretical perspectives that distinguish them from each other?

Margaret Haderer: The market and innovation perspectives are actually quite dominant perspectives.

Martin Auer: Dominant now means in politics, in public discourse?

Margaret Haderer: Yes, in public discourse, in politics, in business. The market perspective assumes that the problem with climate-unfriendly structures is that the true costs, i.e. ecological and social costs, of climate-unfriendly living are not reflected: in products, how we live, what we eat, how mobility is designed.

Martin Auer: So all of that isn't priced in, it's not visible in the price? That means society pays a lot.

Margaret Haderer: Exactly. Society pays a lot, but a lot is also externalized to future generations or towards the Global South. Who bears the environmental costs? It's often not us, but people who live somewhere else.

Martin Auer: And how does the market perspective want to intervene now?

Margaret Haderer: The market perspective proposes creating cost truth by pricing in externalized costs. CO2 pricing would be a very concrete example of this. And then there is the challenge of implementation: How do you calculate the CO2 emissions, do you reduce it to just CO2 or do you price in social consequences. There are different approaches within this perspective, but the market perspective is about creating true costs. This works better in some areas than others. This may work better with food than in areas where the logic of pricing is inherently problematic. So if you now take on work that is actually not profit-oriented, for example care, how do you create true costs? The value of nature would be an example, is it good to price in relaxation?

Martin Auer: So are we already criticizing the market perspective?

Margaret Haderer: Yes. We look at every perspective: what are the diagnoses, what are the possible solutions, and what are the limits. But it's not about playing off the perspectives against each other, it probably needs the combination of all four perspectives.

Martin Auer: The next thing would then be the innovation perspective?

The innovation perspective

Margaret Haderer: Exactly. We argued a lot about whether it isn't part of the market perspective anyway. Nor can these perspectives be sharply separated. One tries to conceptualize something that is not clearly defined in reality.

Martin Auer: But isn't it just about technical innovations?

Margaret Haderer: Innovation is mostly reduced to technical innovation. When we are told by some politicians that the true way to deal with the climate crisis lies in more technological innovation, that is a widespread perspective. It's also quite convenient because it promises that you have to change as little as possible. Automobility: Away from the combustion engine (now that “away” is a bit wobbly again) towards e-mobility means, yes, you also have to change infrastructures, you even have to change quite a lot if you want to make alternative energy available, but mobility remains for the end consumer, the end consumer as she was.

Martin Auer: Every family has one and a half cars, only now they are electric.

Margaret Haderer: Yes. And that's where the market perspective is quite close, because it relies on the promise that technological innovations will prevail on the market, sell well, and that something like green growth could be generated there. That doesn't work so well because there are rebound effects. This means that technological innovations usually have subsequent effects that are often harmful to the climate. To stay with e-cars: They are resource-intensive in production, and that means that the emissions you get down there will almost certainly not be redeemed. Now, within the innovation debate, there are also those who say: we have to move away from this narrow concept of technological innovation towards a broader concept, namely social-technological innovations. What is the difference? With technical innovation, which is close to the market perspective, the idea prevails that the green product will prevail - ideally - and then we will have green growth, we don't have to change anything about the growth itself. The people who advocate socio-technical or socio-ecological innovations say we have to pay much more attention to the social effects we want to produce. If we want to have climate-friendly structures, then we can't just look at what is now penetrating the market, because the logic of the market is the logic of growth. We need an expanded concept of innovation that takes the ecological and social effects into account much more.

Martin Auer: For example, not only using different building materials, but also living differently, different living structures, more common rooms in houses so that you can get by with less material, a drill for the whole house instead of one for each family.

Margaret Haderer: Exactly, that's a really great example of how other everyday practices make you live, consume and be mobile more resource-intensive. And this living example is a great example. For a long time it was assumed that the passive house on the green field was the future of sustainability. It is a technological innovation, but many things were not considered: the green field was not considered for a long time, or what mobility that implies - that is usually only possible with a car or two cars. Social innovation sets normative goals, such as climate-friendly structures, and then tries to focus on technologies in combination with practices that promise to achieve this normative goal. Sufficiency always plays a role. So don't necessarily build new, but renovate the existing one. Dividing common rooms and making the apartments smaller would be a classic social innovation.

The deployment perspective

Then there's the next perspective, the deployment perspective. It wasn't easy to agree on either. The provision perspective borders on social innovation, which is committed to normative goals. The neighborhood consists in the fact that the provision perspective also questions the common good or the social benefit of something and does not automatically assume that what prevails on the market is also socially good.

Martin Auer: Deployment is now also such an abstract concept. Who provides what for whom?

Margaret Haderer: When providing them, one asks oneself the fundamental question: how do the goods and services get to us? What else is there beyond the market? When we consume goods and services, it's never just the market, there's still a lot of public infrastructure behind it. For example, the roads that are built publicly bring us the goods from XYZ, which we then consume. This perspective assumes that the economy is bigger than the market. There is also a great deal of unpaid work, mostly done by women, and the market would not function at all if there were not also less market-oriented areas, such as a university. You can rarely run them profit-oriented, even if there are such tendencies.

Martin Auer: So roads, the power grid, sewage system, garbage disposal...

Margaret Haderer: …kindergartens, retirement homes, public transport, medical care and so on. And against this background, a fundamentally political question arises: How do we organize public supply? What role does the market play, what role should it play, what role should it not play? What would be the advantages and disadvantages of more public supply? This perspective focuses on the state or even the city, not only as someone who creates market conditions, but who always shape the common good in one way or another. When designing climate-unfriendly or climate-friendly structures, political design is always involved. A problem diagnosis is: How is services of general interest understood? There are forms of work that are totally socially relevant, such as care, and are actually resource-intensive, but enjoy little recognition.

Martin Auer: Resource extensive means: you need few resources? So the opposite of resource-intensive?

Margaret Haderer: Exactly. However, when the focus is on the market perspective, these forms of work are often rated poorly. You get bad pay in these areas, you get little social recognition. Nursing is such a classic example. The provision perspective emphasizes that jobs such as supermarket cashier or caretaker are extremely important for social reproduction. And against this background, the question arises: Shouldn't this be reassessed if climate-friendly structures are the goal? Wouldn't it be important to rethink work against the background: What does that actually do for the community?

Martin Auer: Many of the needs that we buy things to satisfy can also be satisfied in other ways. I can buy such a home massager or I can go to a massage therapist. The real luxury is the masseur. And through the provision perspective, one could steer the economy more in the direction that we replace needs less with material goods and more with personal services.

Margaret Haderer: Yes, exactly. Or we can look at swimming pools. In recent years there has been a tendency, especially in the countryside, for everyone to have his or her own swimming pool in the backyard. If you want to create climate-friendly structures, you actually need a municipality, a city or a state that puts a stop to it because it draws off a lot of groundwater and provides a public swimming pool.

Martin Auer: So a communal one.

Margaret Haderer: Some speak of communal luxury as an alternative to private luxury.

Martin Auer: It is always assumed that the climate justice movement tends towards asceticism. I think we really have to emphasize that we want luxury, but a different kind of luxury. So communal luxury is a very nice term.

Margaret Haderer: In Vienna, a lot is made publicly available, kindergartens, swimming pools, sports facilities, public mobility. Vienna is always greatly admired from the outside.

Martin Auer: Yes, Vienna was already exemplary in the interwar period, and it was politically consciously designed that way. With the community buildings, parks, free outdoor pools for children, and there was a very conscious policy behind it.

Margaret Haderer: And it was also very successful. Vienna keeps getting awards as a city with a high quality of life, and doesn't get these awards because everything is provided privately. Public provision has a major impact on the high quality of life in this city. And it's often cheaper, viewed over a longer period of time, than if you leave everything to the market and then have to pick up the pieces, so to speak. Classic example: the USA has a privatized health care system, and no other country in the world spends as much on health as the USA. They have relatively high public spending despite the dominance of private players. That's just not very purposeful spending.

Martin Auer: So the provision perspective would mean that the areas with public supply would also be further expanded. Then the state or the municipality really has an influence on how it is designed. One problem is that roads are made public, but we don't decide where roads are built. See Lobau tunnel for example.

Margaret Haderer: Yes, but if you were to vote on the Lobau tunnel, a large part would probably be in favor of building the Lobau tunnel.

Martin Auer: It's possible, there are a lot of interests involved. Nevertheless, I believe that people can achieve reasonable results in democratic processes if the processes are not influenced by interests that, for example, invest a lot of money in advertising campaigns.

Margaret Haderer: I would disagree. Democracy, whether representative or participatory, does not always work in favor of climate-friendly structures. And you probably have to come to terms with that. Democracy is no guarantee for climate-friendly structures. If you were to vote now on the internal combustion engine - there was a survey in Germany - 76 percent would supposedly be against the ban. Democracy can inspire climate-friendly structures, but they can also undermine them. The state, the public sector, can also promote climate-friendly structures, but the public sector can also promote or cement climate-unfriendly structures. The history of the state is one that has always promoted fossil fuels over the last few centuries. So both democracy and the state as an institution can be both a lever and a brake. It is also important from the perspective of provision that you counteract the belief that whenever the state is involved, it is good from a climate perspective. Historically it wasn't like that, and that's why some people quickly realize that we need more direct democracy, but it's not automatic that it leads to climate-friendly structures.

Martin Auer: This is certainly not automatic. I think it depends very much on what insight you have. It is striking that we have a few communities in Austria that are far more climate-friendly than the state as a whole. The further down you go, the more insight people have, so they can better assess the consequences of one or the other decision. Or California is far more climate-friendly than the US as a whole.

Margaret Haderer: It is true for the USA that cities and also states such as California often play a pioneering role. But if you look at environmental policy in Europe, the supranational state, i.e. the EU, is actually the organization that sets the most standards.

Martin Auer: But if I now look at the Citizens’ Climate Council, for example, they came up with very good results and made very good suggestions. That was just a process where you didn't just vote, but where you came to decisions with scientific advice.

Margaret Haderer: I do not want to argue against participatory processes, but decisions must also be made. In the case of the combustion engine, it would have been good if it had been decided at EU level and then had to be implemented. I think it takes a both-and. Political decisions are needed, such as a climate protection law, which are then also enacted, and of course participation is also needed.

The society perspective

Martin Auer: This brings us to the social and natural perspective.

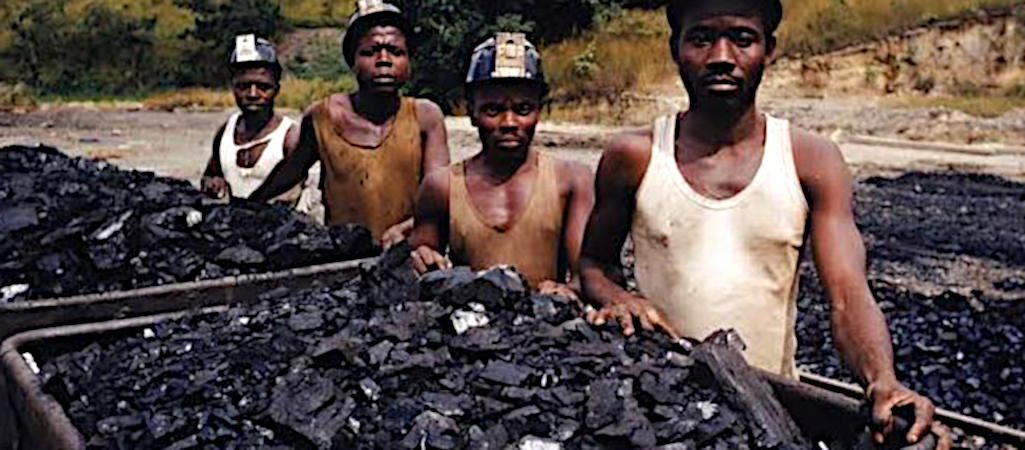

Margaret Haderer: Yes, that was primarily my responsibility, and it's about in-depth analysis. How did these structures, the social spaces in which we move, become what they are, how did we actually get into the climate crisis? So this now goes deeper than “too much greenhouse gases in the atmosphere”. The social perspective also asks historically how we got there. Here we are right in the middle of the history of modernity, which was very Europe-centric, the history of industrialization, capitalism and so on. This brings us to the “Anthropocene” debate. The climate crisis has a long history, but there was a big acceleration after World War II with the normalization of fossil fuels, automobility, urban sprawl, etc. That's a really short story. Structures emerged that were expansive, resource-intensive and socially unjust, also in global terms. That has a lot to do with the reconstruction after the Second World War, with Fordism1, the establishment of consumer societies driven by fossil energy. This development also went hand in hand with colonization and extraction2 in other areas. So it wasn't evenly distributed. What was worked out here as a good standard of living could never be universalized in terms of resources. The good life with a single-family house and car needs a lot of resources from elsewhere, so that somewhere else someone else is actually not doing so well, and also has a gender perspective. The “Anthropocene” is not man per se. “Human” [responsible for the Anthropocene] lives in the Global North and is predominantly male. The Anthropocene is based on gender inequalities and global inequalities. The effects of the climate crisis are unevenly distributed, but so is the cause of the climate crisis. It wasn't "man as such" that was involved. You have to take a close look at which structures are responsible for us being where we are. It's not about moralizing. However, one recognizes that issues of justice are always decisive for overcoming the climate crisis. Justice between generations, justice between men and women and global justice.

Martin Auer: We also have major inequalities within the Global South and within the Global North. There are people for whom climate change is less of a problem because they can protect themselves well against it.

Margaret Haderer: For example with air conditioning. Not everyone can afford them, and they exacerbate the climate crisis. I can make it cooler, but I use more energy and someone else bears the costs.

Martin Auer: And I'll heat up the city right away. Or I can afford to drive to the mountains when it gets too hot or fly somewhere else entirely.

Margaret Haderer: Second home and stuff, yes.

Martin Auer: Can one actually say that different images of humanity play a role in these different perspectives?

Margaret Haderer: I would speak of different ideas about society and social change.

Martin Auer: So there is, for example, the image of the “Homo oeconomicus”.

Margaret Haderer: Yes, we discussed that too. So "homo oeconomicus" would be typical for the market perspective. The person who is socially conditioned and dependent on society, on the activities of others, would then be the image of the provision perspective. From the perspective of society, there are many images of people, and that's where it becomes more difficult. "Homo socialis" could be said for the social perspective and also the provision perspective.

Martin Auer: Is the question of the “actual needs” of human beings raised in the different perspectives? What do people really need? I don't necessarily need a gas heater, I have to be warm, I need heat. I need food, but it can be either way, I can eat meat or I can eat vegetables. In the field of health, nutritional science is relatively unanimous about what people need, but does this question also exist in a broader sense?

Margaret Haderer: Each perspective implies answers to this question. The market perspective assumes that we make rational decisions, that our needs are defined by what we buy. In the provision and society perspectives, it is assumed that what we think of as needs are always socially constructed. Needs are also generated, through advertising and so on. But if climate-friendly structures are the goal, then there may be one or two needs that we can no longer afford. In English there is a nice distinction between “needs” and “wants” – i.e. needs and desires. For example, there is a study that the average apartment size for a single-family household immediately after the Second World War, which was already considered luxurious at the time, is a size that could be universalized quite well. But what happened in the single-family house sector from the 1990s onwards – the houses have gotten bigger and bigger – something like that cannot be universalized.

Martin Auer: I think universal is the right word. A good life for everyone must be for everyone, and first of all the basic needs have to be satisfied.

Margaret Haderer: Yes, there are already studies on this, but there is also a critical debate as to whether it can really be determined in this way. There are sociological and psychological studies on this, but it is politically difficult to intervene, because at least from the market perspective it would be an encroachment on individual freedom. But not everyone can afford their own pool.

Martin Auer: I believe that growth is also viewed very differently from the individual perspectives. From the market perspective it is an axiom that the economy has to grow, on the other hand there are sufficiency and degrowth perspectives that say it must also be possible to say at a certain point: Well, now we have enough, that's enough, it doesn't have to be more.

Margaret Haderer: The accumulation imperative and also the growth imperative are inscribed in the market perspective. But even in the perspective of innovation and provision, one does not assume that growth will absolutely stop. The point here is: Where should we grow and where should we not grow or should we shrink and "exnovate", i.e. reverse innovations. From the societal perspective, you can see that on the one hand our standard of living is based on growth, but at the same time it is also highly destructive, historically speaking. The welfare state, as it was built, is based on growth, for example the pension security systems. The broad masses also benefit from growth, and that makes the creation of climate-friendly structures very challenging. People get scared when they hear about post-growth. Alternative offers are needed.

Martin Auer: Thank you very much, dear Margret, for this interview.

This interview is part 2 of ours Series on the APCC Special Report "Structures for a climate-friendly living".

The interview can be heard in our podcast ALPINE GLOW.

The report will be published as an open access book by Springer Spectrum. Until then, the respective chapters are on the CCCA home page available.

Photos:

Cover photo: Urban Gardening on the Danube Canal (wien.info)

Prices at a gas station in the Czech Republic (author: unknown)

monorail. LM07 via pixabay

Children's outdoor pool Margaretengurtel, Vienna, after 1926. Friz Sauer

Miners in Nigeria. Environmental Justice Atlas, CC BY 2.0

1 Fordism, which developed after the First World War, was based on highly standardized mass production for mass consumption, assembly line work with work steps divided into the smallest units, strict work discipline and a desired social partnership between workers and entrepreneurs.

2 exploitation of raw materials

This post was created by the Option Community. Join in and post your message!