by Martin Auer

Should climate policy concentrate purely on reducing CO2 emissions, or should it embed the climate problem in a concept of transformation for society as a whole?

Political scientist Fergus Green from University College London and sustainability researcher Noel Healy from Salem State University in Massachusetts have published a study on this question in the journal One Earth: How inequality fuels climate change: The climate case for a Green New Deal1 In it, they deal with the criticism that representatives of a CO2-centric policy level at various concepts that embed climate protection in broader social programs. These critics argue that the broader Green New Deal agenda undermines decarbonization efforts. For example, prominent climate scientist Michael Mann wrote in the journal Nature:

"Giving a climate change movement a shopping list of other laudable social programs risks alienating necessary supporters (such as independent and moderate conservatives) who fear a broader agenda of progressive social change.”2

In their study, the authors show that

- social and economic inequalities are drivers for CO2-intensive consumption and production,

- that the unequal distribution of income and wealth allows wealthy elites to thwart climate protection measures,

- that inequalities undermine public support for climate action,

- and that inequalities undermine the social cohesion necessary for collective action.

This suggests that comprehensive decarbonization is more likely to be achieved when carbon-centric strategies are embedded in a broader program of social, economic and democratic reforms.

This post can only provide a brief summary of the article. Above all, only a small part of the extensive evidence that Green and Healy bring can be reproduced here. A link to the full list follows at the end of the post.

Climate protection strategies, write Green and Healy, originally emerged from a CO2-centric perspective. Climate change was and still is partly understood as a technical problem of excessive greenhouse gas emissions. A number of instruments are proposed, such as subsidies for low-emission technologies and setting technical standards. But the main focus is on the use of market mechanisms: CO2 taxes and emissions trading.

What is a Green New Deal?

Source: Green, F; Healy, N (2022) CC BY 4.0

Green New Deal strategies are not limited to CO2 reduction, but include a wide range of social, economic and democratic reforms. They aim for a far-reaching economic transformation. Of course, the term “Green New Deal” is not unambiguous3. The authors identify the following similarities: Concepts of Green New Deals assign the state a central role in the creation, design and control of markets, namely through state investments in public goods and services, laws and regulations, monetary and financial policy, public procurement and supporting innovation. The aim of these state interventions should be the universal supply of goods and services that satisfy people's basic needs and enable them to lead a prosperous life. Economic inequalities are to be reduced and the consequences of racist, colonialist and sexist oppression made good. Finally, Green New Deal concepts aim to create a broad societal movement, relying both on active participants (particularly organized interest groups of working people and ordinary citizens), and on the passive support of a majority, reflected in election results.

10 mechanisms driving climate change

The knowledge that global warming is exacerbating social and economic inequalities is largely anchored in the climate protection community. Less well known are the causal channels that flow in the opposite direction, that is, how social and economic inequalities affect climate change.

The authors name ten such mechanisms in five groups:

consumption

1. The more income people have, the more they consume and the more greenhouse gases are caused by the production of these consumer goods. Studies estimate that emissions from the richest 10 percent account for up to 50% of global emissions. Large savings in emissions could thus be achieved if the incomes and wealth of the upper classes were reduced. A study4 of 2009 concluded that 30% of global emissions could be saved if emissions from 1,1 billion of the largest emitters were restricted to the levels of their least polluting member5

Source: Green, F; Healy, N (2022) CC BY 4.0

2. But it's not just the rich's own consumption that leads to higher emissions. The rich tend to flaunt their wealth in a demonstrative manner. As a result, people with lower incomes also try to increase their status by consuming status symbols and finance this increased consumption by working longer hours (e.g. by working overtime or by having all adults in a household work full-time).

But doesn't an increase in lower incomes also lead to higher emissions? Not necessarily. Because the situation of the poor cannot only be improved by getting more money. It can also be improved by making certain climate-friendly produced goods available. If you simply get more money, you will use more electricity, turn the heating up by 1 degree, drive more often, etc made available, etc., the situation of the less well-off can be improved without increasing emissions.

Another perspective is that if the goal is for all people to enjoy the highest possible level of well-being within a safe carbon budget, then consumption by the poorest sections of the population must generally increase. This can tend to lead to a higher demand for energy and thus to higher greenhouse gas emissions. In order for us to remain in a safe carbon budget overall, inequality must be reduced from the top side by restricting the consumption options of the wealthy. What such measures would mean for GDP growth is left open by the authors as an unresolved empirical question.

In principle, say Green and Healy, the energy needs of low-income people are easier to decarbonize as they focus on housing and essential mobility. Much of the energy consumed by the rich comes from air travel6. A decarbonization of air traffic is difficult, expensive and the realization is currently hardly foreseeable. So the positive impact on emissions of reducing the highest incomes could be far greater than the negative impact of increasing the low incomes.

Production

Whether supply systems can be decarbonized depends not only on consumer decisions, but also largely on production decisions by companies and government economic policies.

3. The richest 60% own between 80% (Europe) and nearly 5% of wealth. The poorer half owns XNUMX% (Europe) or less7. That is, a small minority (predominantly white and male) determines with their investments what and how is produced. In the neoliberal era since 1980, many previously state-owned companies have been privatized so that production decisions have been subjected to the logic of private profit rather than the demands of the public good. At the same time, “shareholders” (owners of share certificates, stocks) have gained increasing control over the management of companies, so that their short-sighted, quick profit-oriented interests determine company decisions. This drives managers to shift costs onto others and, for example, to avoid or postpone CO2-saving investments.

4. Capital owners also use their capital to expand political and institutional rules that prioritize profits over all other considerations. The influence of fossil fuel companies on political decisions is widely documented. From 2000 to 2016, for example, US$XNUMX billion was spent lobbying Congress on climate change legislation8. Their influence on public opinion is also documented9 . They also use their power to suppress resistance and criminalize protesters10

Source: Green, F; Healy, N (2022) CC BY 4.0

Democratic control, accountability in politics and business, regulation of companies and financial markets are thus issues that are closely linked to the possibilities for decarbonisation.

politics of fear

5. Fear of losing jobs to climate action, real or perceived, undermines support for decarbonization action11. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the global labor market was in crisis: underemployment, poorly qualified, precarious jobs at the bottom of the labor market, declining union membership, all of this was exacerbated by the pandemic, which exacerbated general insecurity12. Carbon pricing and/or the abolition of subsidies are resented by people on low incomes because they increase the price of everyday consumer goods that generate carbon emissions.

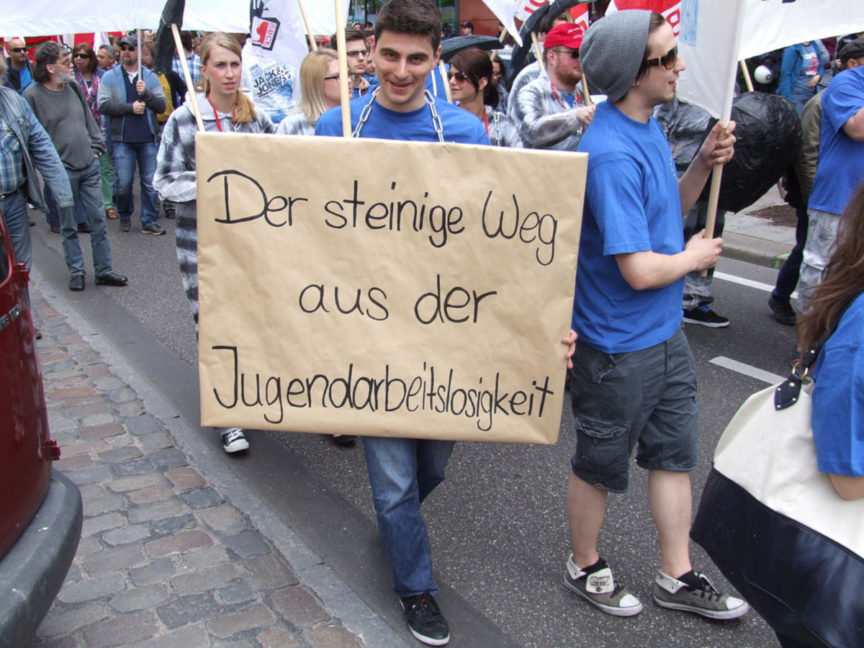

Photo: Claus Ableiter via Wikimedia, CC BY-SA

6. Price increases due to carbon-centric policies - real or perceived - are raising concerns, particularly among the less affluent, and undermining public support for them. This makes it difficult to mobilize the general public for decarbonization measures. Especially groups that are particularly affected by the climate crisis, i.e. that have particularly strong reasons to mobilize, such as women and people of color, are particularly vulnerable to inflationary effects. (For Austria, we could add people of color to people with a migrant background and people without Austrian citizenship.)

A climate-friendly life is not affordable for many

7. Low-income people do not have the financial means or incentives to invest in costly energy-efficient or low-carbon products. For example, in affluent countries, poorer people live in less energy-efficient homes. Since they mostly live in rented apartments, they lack the incentive to invest in energy-efficient improvements. This directly undermines their ability to reduce consumption emissions and contributes to their fears of inflationary effects.

8. Purely CO2-focused policies can also provoke direct counter-movements, such as the yellow vest movement in France, which was directed against the fuel price increases justified by climate policy. Energy and transport price reforms have provoked violent political counter-reactions in numerous countries such as Nigeria, Ecuador and Chile. In areas where carbon-intensive industries are concentrated, plant closures can collapse local economies and shatter deep-rooted local identities, social ties and ties to home.

Lack of cooperation

Recent empirical research links high levels of economic inequality to low levels of social trust (trust in other people) and political trust (trust in political institutions and organizations).13. Lower levels of trust are associated with lower support for climate action, particularly for fiscal instruments14. Green and Healy see two mechanisms at work here:

9. Economic inequality leads – this can be proven – to more corruption15. This reinforces the general perception that political elites only pursue their own interests and those of the rich. As such, citizens will have little confidence if they are promised that short-term restrictions will lead to long-term improvements.

10. Second, economic and social inequality lead to a division in society. The wealthy elites can physically isolate themselves from the rest of society and protect themselves from social and environmental ills. Because the wealthy elites have disproportionate influence over cultural production, particularly the media, they can use this power to foment social divisions between different social groups. For example, wealthy conservatives in the US have promoted the notion that the government takes from the “hard-working” white working class to hand out handouts to the “undeserving” poor, such as immigrants and people of color. (In Austria, this corresponds to the polemics against social benefits for “foreigners” and “asylum seekers”). Such views weaken the social cohesion necessary for cooperation between social groups. This suggests that a mass social movement, such as is needed for rapid decarbonization, can only be created by strengthening social cohesion between different societal groups. Not only by demanding an equitable distribution of material resources, but also by mutual recognition that allows people to see themselves as part of a common project that achieves improvements for all.

What are the responses from Green New Deals?

Thus, since inequality directly contributes to climate change or hinders decarbonization in various ways, it is reasonable to assume that concepts of broader social reforms can promote the fight against climate change.

The authors examined 29 Green New Deal concepts from five continents (predominantly from Europe and the USA) and divided the components into six policy bundles or clusters.

Source: Green, F; Healy, N (2022) CC BY 4.0

Sustainable social care

1. Policies for sustainable social provision strive for all people to have access to goods and services that meet basic needs in a sustainable manner: thermally efficient housing, emission- and pollution-free household energy, active and public mobility, sustainably produced healthy food, safe drinking water. Such measures reduce inequality in care. In contrast to purely CO2-centric policies, they enable poorer classes to have access to low-carbon everyday products without burdening their household budget even more (Mechanism 2) and thus do not provoke any resistance from them (Mechanism 7). Decarbonising these supply systems also creates jobs (e.g. thermal renovation and construction work).

Financial security

2. Green New Deal concepts strive for financial security for the poor and those at risk of poverty. For example, through a guaranteed right to work; a guaranteed minimum income sufficient to live on; free or subsidized training programs for climate-friendly jobs; safe access to health care, social welfare and childcare; improved social security. Such policies can reduce opposition to climate action on grounds of financial and social insecurity (Mechanisms 5 to 8). Financial security allows people to understand decarbonization efforts without fear. As they also offer support to workers in declining carbon-intensive industries, they can be seen as an extended form of 'just transition'.

change in power relations

3. The authors identify efforts to change power relations as the third cluster. Climate policy will be more effective the more it restricts the concentration of wealth and power (mechanisms 3 and 4). Green New Deal concepts aim to reduce the wealth of the rich: through more progressive income and wealth taxes and by closing tax loopholes. They call for a power shift away from shareholders towards workers, consumers and local communities. They strive to reduce the influence of private money on politics, for example by regulating lobbying, limiting campaign spending, restricting political advertising or public funding of election campaigns. Because power relations are also racist, sexist, and colonialist, many Green New Deal concepts call for material, political, and cultural justice for marginalized groups. (For Austria this would mean, among other things, ending the political exclusion of over a million working people who are not entitled to vote).

Photo: Martin Auer

CO2-centric measures

4. The fourth cluster includes CO2-centric measures such as CO2 taxes, regulation of industrial emitters, regulation of the supply of fossil fuels, subsidies for the development of climate-neutral technologies. Insofar as they are regressive, i.e. have a greater impact on lower incomes, this should at least be compensated for by measures from the first three clusters.

redistribution by the state

5. A striking commonality of Green New Deal concepts is the broad role that government spending is expected to play. The taxes on CO2 emissions, income and capital discussed above are to be used to finance the required measures for sustainable social provision, but also to encourage technological innovation. Central banks should favor low-carbon sectors with their monetary policy, and green investment banks are also proposed. The national accounting and also the accounting of the companies should be structured according to sustainability criteria. It is not the GDP (gross domestic product) that should serve as an indicator of successful economic policy, but the Genuine Progress Indicator16 (indicator of real progress), at least as a supplement.

International cooperation

6. Only a few of the examined Green New Deal concepts include aspects of foreign policy. Some propose border adjustments to protect more sustainable production from competition from countries with less stringent sustainability regulations. Others focus on international regulations for trade and capital flows. Since climate change is a global problem, the authors believe that Green New Deal concepts should include a global component. These could be initiatives to make sustainable social provision universal, to universalize financial security, to change global power relations, to reform international financial institutions. Green New Deal concepts could have the foreign policy goals of sharing green technologies and intellectual property with poorer countries, promoting trade in climate-friendly products and restricting trade in CO2-heavy products, preventing cross-border financing of fossil projects, closing tax havens , grant debt relief and introduce global minimum tax rates.

Assessment for Europe

Inequality is particularly high among high-income countries in the United States. In European countries it is not so pronounced. Some political actors in Europe consider Green New Deal concepts to be able to win a majority. The "European Green Deal" announced by the EU Commission may seem modest compared to the models outlined here, but the authors see a break with the previous purely CO2-centric approach to climate policy. Experiences in some EU countries suggest that such models can be successful with voters. For example, the Spanish Socialist Party increased its majority by 2019 seats in the 38 elections with a strong Green New Deal program.

Note: Only a small selection of references has been included in this summary. The complete list of studies used for the original article can be found here: https://www.cell.com/one-earth/fulltext/S2590-3322(22)00220-2#secsectitle0110

Cover photo: J. Sibiga via flickr, C.C WOULD

Spotted: Michael Bürkle

1 Green, Fergus; Healy, Noel (2022): How inequality fuels climate change: The climate case for a Green New Deal. In: One Earth 5/6:635-349. On-line: https://www.cell.com/one-earth/fulltext/S2590-3322(22)00220-2

2 Mann, Michael E. (2019): Radical reform and the green new deal. In: Nature 573_ 340-341

3 And does not necessarily coincide with the term "social-ecological transformation", although there are certainly overlaps. The term is based on the "New Deal", the economic program of FD Rooseveldt, which was intended to combat the economic crisis of the 1930s in the USA. Our cover photo shows a sculpture that commemorates this.

4 Chakravarty S. et al. (2009): Sharing global CO2 emission reductions among one billion high emitters. In: Proc. national Acad. science US 106: 11884-11888

5 Compare also our report on the current one Climate Inequality Report 2023

6 For the wealthiest tenth of the UK population, air travel accounted for 2022% of a person's energy use in 37. A person in the richest tenth used as much energy on air travel as a person in the poorest two tenths on all living expenses: https://www.carbonbrief.org/richest-people-in-uk-use-more-energy-flying-than-poorest-do-overall/

7 Chancel L, Piketty T, Saez E, Zucman G (2022): World Inequality Report 2022. Online: https://wir2022.wid.world/executive-summary/

8 Brulle, RJ (2018): The climate lobby: a sectoral analysis of lobbying spending on climate change in the USA, 2000 to 2016. Climatic Change 149, 289–303. On-line: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10584-018-2241-z

9 Oreskes N.; Conway EM (2010); Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. Bloomsbury Press,

10 Scheidel Armin et al. (2020): Environmental conflicts and defenders: a global overview. In: Glob. environment Chang. 2020; 63: 102104, Online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959378020301424?via%3Dihub

11 Vona, F. (2019): Job losses and political acceptability of climate policies: why the 'job-killing' argument is so persistent and how to overturn it. In: Clim. Policy. 2019; 19:524-532. On-line: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14693062.2018.1532871?journalCode=tcpo20

12 In April 2023, 2,6 million young people under 25 were unemployed in the EU, or 13,8%: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/16863929/3-01062023-BP-EN.pdf/f94b2ddc-320b-7c79-5996-7ded045e327e

13 Rothstein B., Uslaner EM (2005): All for all: equality, corruption, and social trust. In: World Politics. 2005; 58:41-72. On-line: https://muse-jhu-edu.uaccess.univie.ac.at/article/200282

14 Kitt S. et al. (2021): The role of trust in citizen acceptance of climate policy: comparing perceptions of government competence, integrity and value similarity. In: Ecol. econ. 2021; 183: 106958. Online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921800921000161

15 Uslaner EM (2017): Political trust, corruption, and inequality. in: Zmerli S. van der Meer TWG Handbook on Political Trust: 302-315

16https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indikator_echten_Fortschritts

This post was created by the Option Community. Join in and post your message!