Steel and cement are big climate killers. The iron and steel industry is responsible for around 11 percent of global CO2 emissions, and the cement industry for around 8 percent. The idea of replacing reinforced concrete in construction with a more climate-friendly building material is obvious. So should we rather build with wood? Are we tired of this? Is wood really CO2 neutral? Or could we even store the carbon that the forest takes out of the atmosphere in wooden buildings? Would that be the solution to all our problems? Or are there limitations like many technological solutions?

Martin Auer from SCIENTISTS FOR FUTURE discussed this with dr Johannes Tintner-Olifiers maintained by the Institute for Physics and Materials Science at the University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Sciences in Vienna.

JOHANNES TINTNER-OLIFIERS: It is clear that we have to reorient ourselves when it comes to building materials. The emissions that the cement industry and the steel industry are currently generating are at a very high level - with all due respect for the measures that the cement industry is taking to reduce CO2 emissions. A lot of research is being done on how to produce cement in a climate-neutral manner and also on how to replace the binder cement with other binders. Work is also being done on separating and binding CO2 in the chimney during cement production. You can do it with enough energy. Chemically, converting this CO2 into plastic with hydrogen works. The question is: what do you do with it then?

The building material cement will still be important in the future, but it will be an extremely luxury product because it consumes a lot of energy - even if it is renewable energy. From a purely economic point of view, we won't want to afford it. The same applies to steel. No major steel mill is currently running entirely on renewable energy, and we don't want to afford that either.

We need building materials that require significantly less energy. There aren't very many, but if we look back at history, the range is familiar: clay building, timber building, stone. These are building materials that can be mined and used with relatively little energy. In principle, that is possible. But the wood industry is currently not CO2-neutral. Wood harvesting, wood processing, wood industry work with fossil energy. The sawmill industry is relatively still the best link in the chain, because many companies operate their own combined heat and power plants with the enormous amounts of sawdust and bark that they generate. A whole range of synthetic materials based on fossil raw materials are used in the wood industry, for example for gluing, . There's a lot of research going on, but that's the situation at the moment.

Despite this, the carbon footprint of wood is much better than that of reinforced concrete. Rotary kilns for cement production sometimes burn heavy oil. The cement industry causes 2 percent of CO8 emissions globally. But the fuels are only one aspect. The second side is the chemical reaction. Limestone is essentially a compound of calcium, carbon and oxygen. When converting to cement clinker at high temperatures (approx. 2°C), the carbon is released as CO1.450.

MARTIN AUER: A lot is being thought about how to extract carbon from the atmosphere and store it in the long term. Could wood as a building material be such a store?

JOHANNES TINTNER-OLIFIERS: In principle, the calculation is correct: If you take wood from the forest, manage this area sustainably, forest grows again there, and the wood is not burned but processed in buildings, then the wood is stored there and that CO2 not in the atmosphere. So far, so right. We know that wooden structures can get very old. In Japan there are very famous wooden buildings that are over 1000 years old. We can learn an incredible amount from environmental history.

Left: Hōryū-ji, “Temple of Teaching Buddhas' in Ikaruga, Japan. According to a dendrochronological analysis, the wood of the central column was felled in 594.

Photos: 663highlands via Wikimedia

Right: Stave Church in Urnes, Norway, built in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Photos: Michael L. Rieser via Wikimedia

Humans used to use wood far more wisely than we do today. An example: The technically strongest zone in a tree is the branch connection. It must be particularly stable so that the branch does not break off. But we don't use that today. We bring the wood to the sawmill and saw off the branch. For the construction of ships in the early modern period, a special search was made for trees with the right curvature. Some time ago I had a project about traditional resin production from black pines, the "Pechen". It was difficult to find a blacksmith who could make the necessary tool - an adze. The pecher made the handle himself and looked for a suitable dogwood bush. He then had this tool for the rest of his life. Sawmills process a maximum of four to five tree species, some even specialize in just one species, primarily larch or spruce. In order to use wood better and more intelligently, the wood industry would have to become much more artisan, use human labor and human know-how and produce fewer mass-produced goods. Of course, producing an adze handle as a one-off would be economically problematic. But technically, such a product is superior.

Left: Reconstruction of a Neolithic scoring plow that takes advantage of the natural forking of the wood.

Photos: Wolfgang Clean via Wikimedia

Right: adze

Photos: Razbak via Wikimedia

MARTIN AUER: So wood isn't as sustainable as one would normally think?

JOHANNES TINTNER-OLIFIERS: The EU Commission recently classified the wood industry in bulk and as sustainable. This has caused a lot of criticism, because the use of wood is only sustainable if it does not reduce the total forest stock. Forest use in Austria is currently sustainable, but this is only because we do not need these resources as long as we work with fossil raw materials. We also outsource deforestation in part because we import feed and meat for which forests are cleared elsewhere. We also import charcoal for the grill from Brazil or Namibia.

MARTIN AUER: Would we have enough wood to convert the construction industry?

JOHANNES TINTNER-OLIFIERS: In general, our construction industry is massively bloated. We build too much and recycle far too little. The bulk of the buildings are not designed for recycling. If we wanted to replace the currently installed amounts of steel and concrete with wood, we would not have enough for it. A big problem is that structures today have a relatively short lifespan. Most reinforced concrete buildings are demolished after 30 to 40 years. This is a waste of resources that we cannot afford. And as long as we haven't solved this problem, it won't help to replace the reinforced concrete with wood.

If, at the same time, we want to use a lot more biomass for energy generation and give back a lot more biomass as building material and a lot more land to agriculture - that's just not possible. And if wood is declared as CO2-neutral in bulk, then there is a risk that our forests will be felled. They would then grow back in 50 or 100 years, but over the next few years this would fuel climate change just as much as the consumption of fossil raw materials. And even if wood can be stored in buildings for a long time, a large part is incinerated as sawing waste. There are many processing steps and ultimately only a fifth of the wood is actually installed.

MARTIN AUER: How high could you actually build with wood?

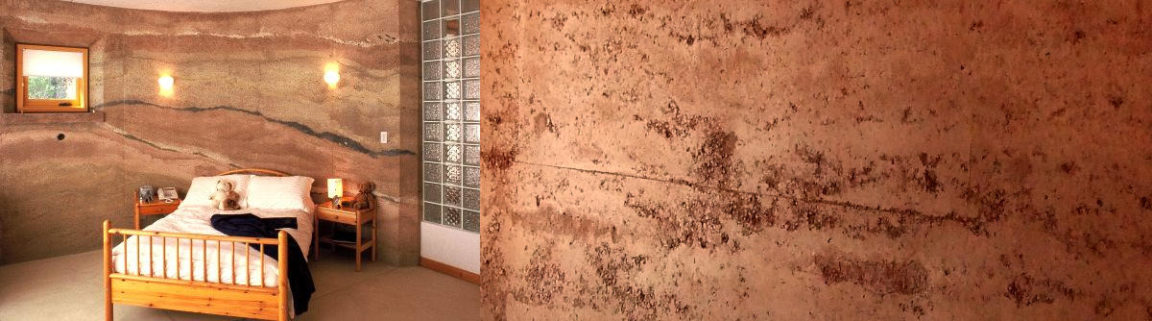

JOHANNES TINTNER-OLIFIERS: A high-rise building with 10 to 15 floors can certainly be built using timber construction. Not all parts of the building have to have the same load-bearing capacity as reinforced concrete. Clay could be used in interior design in particular. Similar to concrete, clay can be filled into formwork and tamped down. Unlike bricks, rammed earth does not need to be heated. Especially if it can be extracted locally, clay has a very good CO2 balance. There are already companies that produce prefabricated parts made of clay, straw and wood. This is certainly a building material of the future. Nevertheless, the main problem remains that we simply build too much. We have to think a lot more about how we renovate old stock. But here, too, the question of the building material is crucial.

Rammed earth walls in interior construction

Photo: author unknown

MARTIN AUER: What would be the plan for big cities like Vienna?

JOHANNES TINTNER-OLIFIERS: When it comes to multi-storey residential buildings, there is no reason not to use wood or wood-clay construction. This is currently a question of price, but if we price in CO2 emissions, then the economic realities change. Reinforced concrete is an extreme luxury product. We will need it because, for example, you cannot build a tunnel or a dam using wood. Reinforced concrete for three- to five-storey residential buildings is a luxury that we cannot afford.

However: the forest is still growing, but the growth is becoming smaller, the risk of premature death is increasing, there are more and more pests. Even if we don't take anything, we can't be sure that the forest won't die back. The more global warming increases, the less CO2 the forest can absorb, i.e. the less it can fulfill its intended task of slowing down climate change. This reduces the potential for using wood as a building material even further. But if the relationship is right, then wood can be a very sustainable building material that also meets the requirement of climate neutrality.

Cover photo: Martin Auer, multi-storey residential building in solid wood construction in Vienna Meidling

This post was created by the Option Community. Join in and post your message!